By Pete Hall

Dear New Teacher,

Welcome to the noblest profession on the planet! More than any other field or occupation known to humankind, what you do matters.

Download the PDF version of this letter

Whether you’re entering your teacherhood fresh out of a college program with certificate and degree on your résumé, or you’re choosing teaching as a second- (or third- or seventeenth-) career path, or you’re bringing your experiences and expertise to the classroom as an alternatively certified teacher, look at you. You’ve made it this far, congratulations! Now the real work begins.

You’re going to receive a lot of advice, most of it unsolicited. You’ll also receive copies of the late Harry Wong’s “First Days of School,” Todd Whitaker’s seminal “What Great Teachers Do Differently,” and Bryan Goodwin and Kristin Rouleau’s essential “The New Classroom Instruction That Works,” as well as all sorts of well-intended tips from colleagues, neighbors, relatives, and strangers. You’ll read a lot about education and its strengths and shortcomings online and in your news feed, and your world will become inundated with information about this profession. Absorb everything.

Teaching is a complex, exhausting, wonderful career. You’ll be working entirely with other human beings, which are by nature unique, vexing, and spectacular. Every day is a new day, bringing heretofore unexperienced events, and it’ll keep you on your toes. You’ll need to be ready for just about anything. Scratch that. You’ll need to be ready for precisely anything…and everything. Even things you’ve never heard of and couldn’t possibly imagine.

That’s why I wrote this letter to you. Because no matter how much education changes, no matter what newness descends upon you, no matter what you’re up against, and no matter what challenges present themselves to you, you really only need to know how to do one thing well. One. Here it is:

If you want to be successful, and if you want your students to be successful, then you must simply master the habit of self-reflection and apply it to every element of your professional responsibilities.

Why self-reflection?

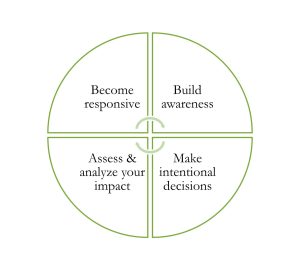

Self-reflection is the skeleton key that opens all the doors that lead to success along your journey. All of them. To effectively self-reflect your way to success, follow the process outlined below. My longtime colleague and co-author Alisa Simeral and I named it “The Reflective Cycle,” and you can read more about it in “Pursuing Greatness” and “Teach, Reflect, Learn” when you’re done with the Wong/Whitaker/Goodwin/Rouleau books mentioned above.

It begins (in the top-right quadrant, moving clockwise) with building awareness, so you’ve got to pay attention. This means you’re clear about what your goal is, what you’re trying to accomplish, or what question you’re trying to address. “Clarity precedes competence,” the late, great Becky DuFour (a teacher before your time, one of the architects of the Professional Learning Community work) used to say; if you want to be good at something, you’ve got to start by being unobfuscatably clear about what it is. Name it, picture it clearly in your mind, write about it if that helps you, tell your dog all about it while you’re on a walk, whatever it takes to become truly and deeply aware of what your target is (for an activity, a lesson, a unit, a course, a career, your legacy, etc.).

The next step is to make intentional decisions as you identify the course of action you’d like to take. In short, you’ve got to orient your mind to the strategy that will likely yield the intended results, then build a plan to implement that strategy. In education, you’re going to be bombarded with curriculum and techniques and research and tools and doohickeys that promise to be “the answer,” and you’ve got to decide what you’re going to do and use. This requires you to be very, very intentional. Great teachers don’t wing it. Do everything you do on purpose.

In the midst of this constant reflection, you’ll get to teach. And build relationships. And create a safe environment. And write lesson plans. And supervise the cafeteria. And meet with your teammates. And analyze data. And bring veggies (okay, let’s be real: lemon bundt cake) when it’s your turn. And connect with families. And monitor the use of AI, tiktok, vaping, sexting, hand gestures, white board markers, and whether or not you have permission to wear jeans. At this point, you implement the strategy, tool, or approach that you’ve very, very intentionally selected in order to meet your goal. Cross your fingers! (And cross your legs, because you won’t be able to use the staff restroom for another 6 hours.)

When the teaching is complete, or while you’re teaching (which is, honestly, an advanced skill, so be patient with yourself as you try to build it), focus your mental energy on assessing and analyzing the impact of your teaching. In this step, you’ve got to identify the direct cause-and-effect relationship between what you did and the results you got. Here, I advise teachers to use the special word “because.” My students learned this much because I taught it like this, for example. Or even this: My students struggled quite a bit with this content because I taught it this way. This step, like the others before it, is a prerequisite for the one you’ll be encouraged to apply a lot:

The ”final” step in the Reflective Cycle is this: Become responsive. Adapt and adjust. Once you’ve adequately scrutinized the impact of your teaching, you can start the process of identifying ways that you can change things (subtly or dramatically) in order to affect the outcomes. Think of the black box of education: if you want to change what comes out of it (student learning), you must change what goes into it (your teaching). You can only make savvy, intentional changes (no winging it, remember!) if you’re really clear about how your teaching resulted in student learning the first time through.

“Final” is in quotation marks in the previous step because once you respond with adaptations, you roll right into the build awareness step of your new, updated goal, and repeat the process until it becomes a consistent, productive, reliable, effective habit.

If you want to be successful, and if you want your students to be successful, then you must simply master the habit of self-reflection and apply it to every element of your professional responsibilities.

Applying self-reflection in the real world of teaching

Here’s how it works in the field, based on advice a couple of expert, veteran teachers shared with me when I asked them for the best tidbits a new teacher should know:

Barbara Gapinski, an elementary teacher and intervention specialist in Painesville, Ohio, understands the enormity of the task of teaching and has a practical approach. “Get good at one thing and build on that,” she says. Below, we’ll walk through the Reflective Cycle with her:

Build Awareness: Looking at the stack of sticky notes and to-do lists sitting next to the long, complex teacher-evaluation rubrics can be overwhelming. So, like in any journey, it’s best to take it one step at a time. Mrs. Gapinski suggests the “one thing” to address first might be the classroom itself. “How your classroom is organized speaks volumes,” she says. If the goal is to increase student learning outcomes, it’s in our collective best interest to design the classroom layout and “feel” in such a way that it efficiently and directly impacts learning and teaching.

Make Intentional Decisions: In order to do this, Mrs. Gapinski sits in the space and envisions the room, full of life and students and bustle. “My tools and materials should be organized so that I can access them efficiently and effectively. The furniture should make sense and have a flow for student movement. Where do students store their materials? How do they turn things in? What will transitions look like?” Questions like these guide Mrs. Gapinski’s reflections and decision-making, and ultimately determine where and how the room is organized. “Everything is placed and situated intentionally,” she says. “Visual clutter, disorganization, obstacles, criss-crossing, and too much stimulation (or too many cutesy things) make engaging with learning challenging for some. If she puts an anchor chart or display on the classroom wall, it’s to facilitate learning and it’s something she plans to use and reference regularly. When it comes to a carpet or gathering area, she considers how students will move from their tables to the carpet and back, and ensures enough physical space for that traffic.

Mrs. Gapinski uses her Smartboard frequently, so she has placed it in a prominent spot so all her students can see it and access it during direct instruction. She also uses centers several times a week, and intentionally situated her furniture to create separation between centers, allowing students to have a defined working space and to reduce congestion. Anchor charts, as they’re created together, are placed on specific walls (depending on the content) and are within reach of students. She leaves adequate space for carpet-time with several alternatives for students who need specific options (a bean-bag and other chairs that allow for choice – or designated – seating).

Assess and Analyze Your Impact: “I can determine if the organization of my physical space is working by observing students in their element (i.e. working), during transitions, and during down time,” Mrs. Gapinski says. After lessons, centers, or activities, she gauges the flow of the class. When things go well (i.e., when students rotate from center to center quickly, smoothly, and without collisions), she celebrates. She also notes items of concern, asking herself: “What do students flock to if they have down time? What do I have to redirect from? Are these things teachable moments or are they things that I, as the classroom leader, need to improve upon?”

Become Responsive: Only by assessing and analyzing the impact of her actions can Mrs. Gapinski make changes to improve the traffic flow, accessibility of resources, and organization of the classroom environment. If students are struggling as they rotate between centers, it may not be the furniture that needs to change. “Do the students know what order to visit the centers?” she asks. “Have I provided a visual to prompt and remind them of the flow? Have I taught, modeled, and practiced this explicitly?” Questions like these generate a brainstorm of next steps and may prompt Mrs. Gapinski to reconfigure the class and/or reteach the expectations. “No matter what,” she says, “I’m always looking for ways to make the classroom an ever more powerful tool in my teaching.”

Eric Dazey, a high school math teacher and dean of students in Corvallis, Oregon, prioritizes his “why” and uses it as the guiding beacon for all his decisions and actions. Let’s see how he uses the Reflective Cycle to guide his work:

Build Awareness: “While we must be passionate about our content, it is even more important that we are passionate about our students,” Mr. Dazey says. To that end, he reminds himself of this daily: “I did not get into this to teach math or to coach football. Those are just the vehicles to support young people in their journey.” The goal for him is clear: Build and maintain strong, meaningful relationships with each and every one of his students.

Make Intentional Decisions: How does Mr. Dazey go about this relationship-building work? “I think about my students’ lives when they’re not in their seats, thinking about who they are, the circumstances they’re in, and where they’re going,” he says. “When I am clear about my intention to connect with students, things are fun.” Notice he emphasizes the word “intention.” This is work that he does on purpose in order to meet the goal he stated above.

Logistically, Mr. Dazey commits to the following every period of every day:

- He greets his students at the door with a smile

- He provides energetic transitions between activities

- He checks in with students 1:1 as often as possible

- He acknowledges every student with eye contact and a personalized comment

- He makes an effort to attend games, concerts, and other events beyond the school day

Assess and Analyze Your Impact: How does Mr. Dazey know if his efforts are working? “With high school kids, so much happens nonverbally,” he says. He can’t determine the strength of his relationships with students just by their words. “I have to look at what my students are saying with their faces, body language, and energy,” he says. “And I have to look at myself, too. What does my body language and tone say to my students?” Not surprisingly, Mr. Dazey is constantly scanning his classroom, gauging the mood and tenor of the period, and keeping a vigilant eye on interactions, engagement, and learning. He is keen to notice when conversations move from guarded to appropriately vulnerable, when content discussions include deeper questions, and when students demonstrate that their learning experience is fun.

Become Responsive: When Mr. Dazey’s metrics show there are stressors or challenges in the room, he is prepared with a response plan. One proactive step is to stay the course. “I try to be there for my students all the time,” he says. “High school kids may not always come to you or tell you they need something, but they see you if you’re consistently there for them.” Mr. Dazey has also learned that each young person needs something a little different from him. “In the past, if I felt like someone wasn’t being seen, I’d go bigger to ensure they knew I noticed them. Some don’t respond well to all that attention, so I work to be steady, understated, and opportunistic to building those relationships.” In the end, Mr. Dazey’s emphasis on intentionally building powerful connections will ensure a strong, trusting setting in which his students will flourish.

Building your reflective muscles

As Mrs. Gapinski and Mr. Dazey have shared, there are tremendous benefits to engaging in reflective thought before, during, and after your teaching. Following the Reflective Cycle is a handy, simple process that can help you develop patterns of thinking – indeed, habits – that you can bring into any new context to increase your effectiveness. Like I tend to say, “The more reflective you are, the more effective you are.”

In order to strengthen these habits, I’ve found it helps to have questions handy to prompt your thinking, so that’s what you’ll find below. I suggest you begin by reflecting in the first two quadrants of the Reflective Cycle before teaching a particular lesson (or taking a particular action), then follow-up by reflecting on the final two quadrants of the Reflective Cycle after teaching a particular lesson (or taking a particular action).

—————————————————————–

BEFORE TEACHING

Build Awareness:

- What is your current challenge?

- What do you want to learn about, implement, or improve upon?

- What is the goal you’d like to accomplish?

- Why is this important to you?

- Where did this big idea originate?

Make Intentional Decisions:

- What ideas or strategies would you like to incorporate and how do they connect with your goal?

- Where might you find additional ideas or guidance on how to implement them?

- How will you decide what strategy to tackle?

- What tools or resources will you need to bring this strategy to life?

- What help do you need (and from whom) with this?

AFTER TEACHING

Assess and Analyze Your Impact:

- To what extent were students successful?

- How do you know? What metric(s) did you use to gauge their success?

- How did your actions, the strategy you implemented, and the manner in which you implemented it impact the results?

- How did students respond because of your teaching?

- How can you keep that cause-and-effect relationship in mind?

Become Responsive:

- What changes will you need to make in order to improve the outcomes next time?

- How do you know?

- What have you learned from this?

- When will you try this approach again?

- Would you like additional feedback? Who can you ask for help?

—————————————————————–

So for now, revel in the newness and the excitement of this new profession, and keep your eyes, ears, heart, and mind open. Remember, you really only need to know how to do one thing well. One, just like I told you at the onset of this letter: If you want to be successful, and if you want your students to be successful, then you must simply master the habit of self-reflection and apply it to every element of your professional responsibilities.

By doing this once, then again, then again and again and again, you can reliably reflect your way to success, no matter what challenges you may encounter in the journey.

You’re going to be great at this. Congratulations and welcome aboard!

Pete Hall

Download the PDF version of this letter

Pete Hall is a former teacher and principal, the author of 12 books on education, and the President/CEO of EducationHall. You can reach him at PeteHall@EducationHall.com.

Stay Up To Date

Stay up to date with the latest news updates and blog posts

Share Article

Share this post with your network and friends

Recent Comments